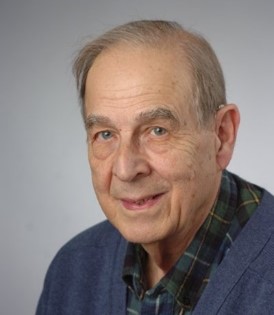

The Great Depression often conjures images of long bread lines, sagebrush rolling over dusty farmlands baren from drought, and sprawling shantytowns full of families struggling through unemployment. For one Syracuse University professor with the College of Arts and Sciences, however, the era was a time where families often got together to support one another, and large pot-luck meals were served with other families in the community.

“I was pretty young during the depression, but I remember extended family all moving together under one roof,” says Dr. Jack Graver, a professor in the mathematics department. “We would have dinners and parties with another family that lived nearby. People found ways to come together and have a good time even when resources were scarce.”

Graver didn’t see himself becoming a mathematician during those early years, instead he had plans to become a naturalist. He found a job as an assistant naturalist during the summers of his junior and senior years of high school and his intent had been to go to Miami University, in Oxford, Ohio, on a program that would let him do his undergraduate studies then attend Duke University, in North Carolina, for his graduate studies to become a naturalist.

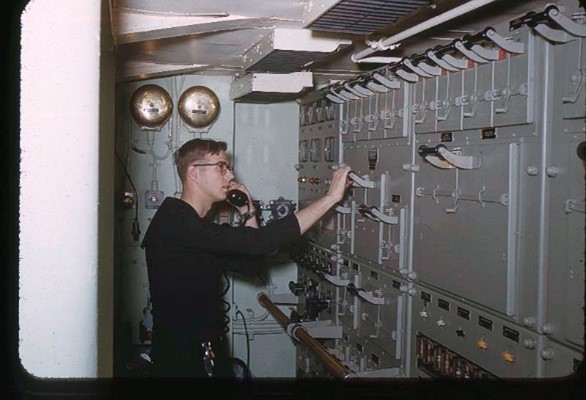

Paying for college would be a hurdle for Graver back then, and he wound up enlisting in the U.S. Navy reserves to take advantage of the scholarship opportunities that military service offered at the time. While not as all-encompassing as today’s Post-9/11 G.I. Bill benefits, the scholarship he received for being in the military was enough to make his academic goals obtainable.

“I served in the Navy reserves for two years. I was a sound-powered communications technician, so I helped maintain the communications we used to talk across ships and things back then,” Graver said. “After my training I was assigned to the Intrepid.”

From Naturalist to Professor of Mathematics

Graver’s journey, like many others, took a completely different path not long after starting college. An advisor had told him that being a naturalist likely would not be intellectually stimulating enough and that, instead, he should consider studying one of the sciences.

“I was interested in science but wasn’t quite sure what field. I was encouraged to study math at first because all the sciences use math, and I ended up loving it,” said Graver.

After Miami University, Graver still followed through on his path of going to graduate school, but instead of Duke University he would attend Indiana University where he would earn both a master’s degree and a doctoral degree in mathematics. Afterwards his career in higher education started when he landed his first teaching position was at Dartmouth College in 1964.

Arrival on Campus and the Student Strike

Graver and his wife, Yana Hanus, later arrived at Syracuse University in 1966, a year after the United States began a large mobilization of ground troops to Vietnam in Southeast Asia. The Civil Rights movement was also in full swing and tensions on campus would steadily grow until 1970 when thousands of students rallied on the quad to protest the U.S. involvement in the war.

The protest grew into a full-blown strike shortly after the Kent State riot, across campus students erected barricades, held rallies, and even took over the administration building for a short time. The tension caused the university to step in and figure out a reasonable course of action.

“One of the things the students wanted was to end the ROTC [Reserve Officer Training Corps] on campus,” said Graver. “They were against the university’s relationship with the Department of Defense back then.”

Syracuse University to this day has one of the longest continuously running ROTC programs in the nation, the units at most other colleges and universities have, as one point in time or another, been shut down for various reasons. Syracuse University, however, opted to keep its ROTC program thanks largely in part to its historic commitment to supporting better educational benefits for veterans, having had two strong advocates for the cause in Chancellors William Tully and Melvin Eggers. Dr. Graver himself was also involved with maintaining the university’s commitment to veterans during those tense times.

“I was involved with campus politics back then with the senate and was on the committee to figure out what to do regarding the ROTC program,” said Graver.

Graver held a unique voice as a military veteran within that committee, which advised the chancellor and the board of trustees to retain the ROTC detachment. The University’s leadership and the student leadership, while on opposing sides of the issue, did manage to manage to keep a civil discourse through most of the turmoil, and many ROTC students themselves were vocal in their support of keeping the program which continues on to this day.

Graver and his wife continue to live in the Syracuse area today after having raised their three children here. Undoubtedly, the campus would look drastically different without the presence of the military-connected community. While he has stepped back from the campus politics in order to help care for his wife, Graver says he’s interested in getting involved once again one day if he is able to do so.