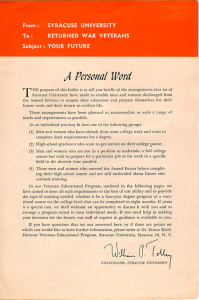

Following the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, Chancellor William P. Tolley issued a bold offer to retuning World War II veterans: apply to Syracuse University and you will be admitted. In what became known as the G.I. Bulge, the community struggled to provide living and classroom space.

News

Enduring Commitment

Syracuse University Today

We have dedicated on-campus resources, The Institute for Veterans and Military Families, degrees designed with veterans in mind, and a community behind it all.

Veterans Resource Center

Student Veterans Organization

Yellow Ribbon

VetSuccess on Campus

OVMA Annual Report 2015-2016

Army ROTC

Colonel Sidney Mashbir, first ROTC commander at Syracuse Univesity

Syracuse University’s Army ROTC Stalwart Battalion traces its lineage to the Students Army Training Corps. The U.S. War Department reorganized the SATC into the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) in 1919 and established a permanent military department at Syracuse University that year.

Colonel Sidney F. Mashbir, the first ROTC commander at Syracuse University, wrote “it should be the aim of Syracuse University to maintain one or more units of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) in order that in time of national emergency there may be a sufficient number of educated men, trained in Military Science and Tactics, to officer and lead intelligently the units of the large armies upon which the safety of the country will depend.”

World War II

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 – better known as the GI Bill – was one of the most significant pieces of legislation ever enacted by the United States Congress. Along with other provisions, it offered a college education to millions of returning veterans, thus opening new opportunities for them and their families, changing the shape of American society and public life, and transforming the very nature of higher education.The response to the bill was far greater than anyone had predicted. Between 1945 and 1950, the GI Bill supported some 2.3 million students, most of whom would never have been able to get a college education without it.

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 – better known as the GI Bill – was one of the most significant pieces of legislation ever enacted by the United States Congress. Along with other provisions, it offered a college education to millions of returning veterans, thus opening new opportunities for them and their families, changing the shape of American society and public life, and transforming the very nature of higher education.The response to the bill was far greater than anyone had predicted. Between 1945 and 1950, the GI Bill supported some 2.3 million students, most of whom would never have been able to get a college education without it.

No university in the country was more closely identified with the GI Bill than Syracuse. Chancellor William P. Tolley served on the Presidential committee whose proposal formed the basis of the legislation. Taking the lead, Tolley also announced Syracuse’s “uniform admissions program,” promising everyone entering the service that there would be places waiting for them at Syracuse when they returned. And when they did return, Syracuse was as good as its word. Although still a small university by national standards, SU ranked first in New York State and 17th in the country in veteran enrollment.

Those years were not easy for anyone – not for the veterans, who were eager (and sometimes impatient) to make up for lost time, and not for the University, which was faced with challenges beyond anything in its history.

Space was at a premium. More than 600 prefab buildings, old barracks, Quonset huts, and trailers covered the campus and surrounding areas. Even so, classrooms were crowded and housing problems were legendary. New programs and curricula had to be developed and social rules had to change. The vets had to adjust to college life, and the students who were already here had to adjust to the vets, whose attitudes were different and whose numbers were overwhelming.

This exhibition, compiled from the University’s Archives and materials contributed by alumni, documents the fact that all those things were accomplished. They were accomplished in what came to be known as Syracuse’s “Can Do Spirit” that prevailed among faculty, staff, and students alike. That spirit of innovation, commitment, and caring – born during the years between 1946 and 1950 – defined a new Syracuse University and set its course to the future. This information is provided by the Syracuse University Archives.